Why Your ADHD Gets Worse Before Your Period

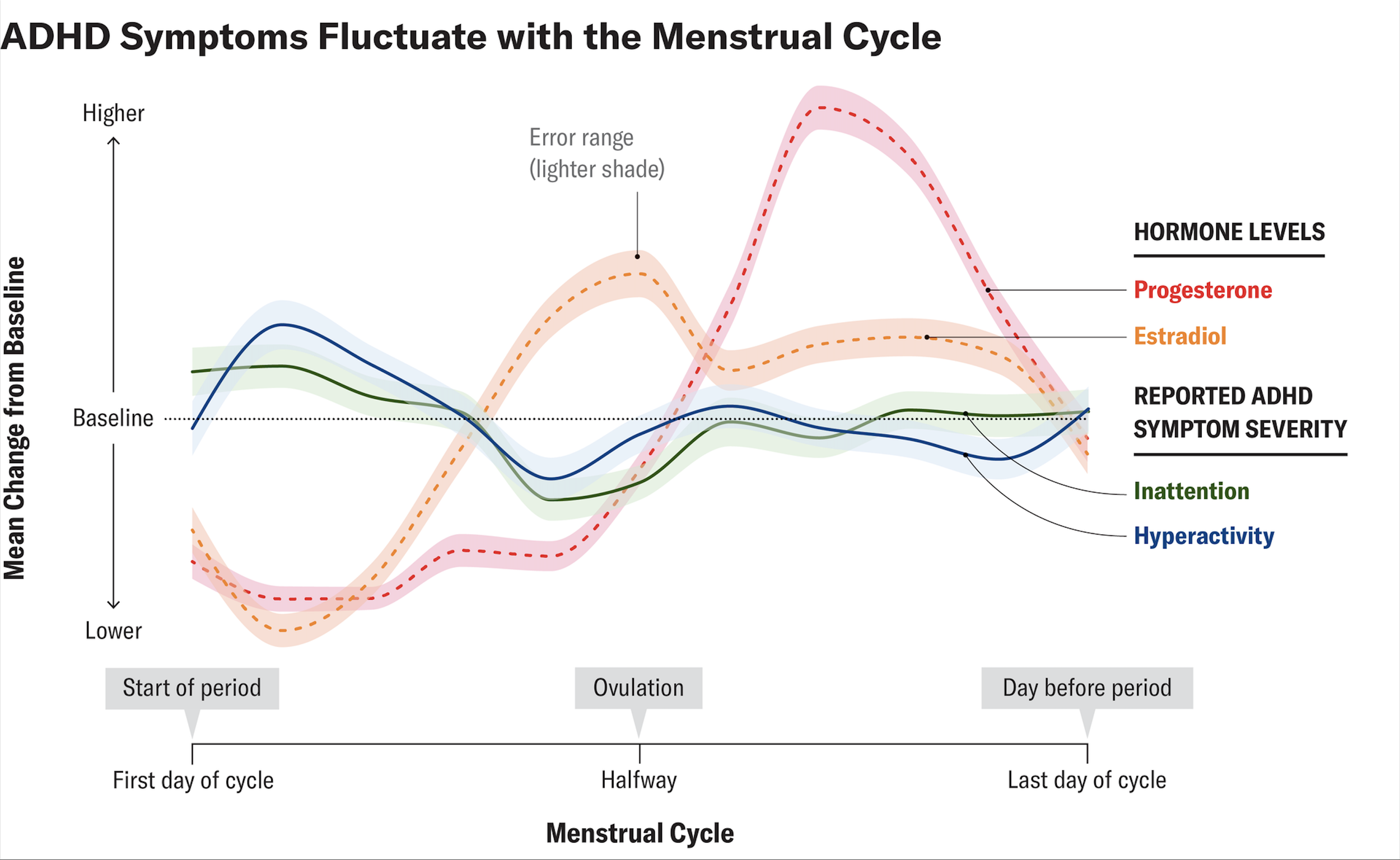

For a lot of people, ADHD symptoms shift across the menstrual cycle. Many notice things feel worse in the week or so before their period (late luteal phase) and in the first few days of bleeding. That timing lines up with a drop in estrogen and changes in progesterone. Since estrogen is involved in supporting dopamine signaling, an estrogen dip can make it harder for the brain to compensate for the dopamine-related challenges that are already part of ADHD. [1]

ADHD and the menstrual cycle

ADHD starts in childhood, but most of the diagnostic criteria and medication research have been based on boys and men. This means sex-specific patterns and menstrual cycle effects flew under the radar for a long time. Over the past decade or so, research and patient experiences have made it clear that many women and people who menstruate notice their inattention, impulsivity, and emotional regulation consistently get worse before their period. [2]

Research has shown that many people with ADHD on stable treatment experience predictable monthly symptom fluctuations—symptoms worsen just before and at the start of their period, medication may feel less effective, and then things improve as the cycle progresses. [3]

A quick look at your cycle

A typical menstrual cycle goes through several hormonal phases, though the exact timing varies from person to person.

Van Anders, S. (2023, July 10). ADHD symptoms can fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. Scientific American.

Follicular phase: Starts on the first day of bleeding; estrogen is initially low and gradually rises as follicles develop. Many people report better energy and mood as estrogen climbs.

Ovulation: Around mid‑cycle, estrogen peaks and some individuals feel more social, motivated, and mentally sharp.

Luteal phase: After ovulation, progesterone rises and estrogen is moderate, then both drop in the late luteal (premenstrual) days.

Premenstrual days: Rapid falls in estrogen and progesterone immediately before menstruation are associated with worsened mood, cognitive changes, and increased ADHD symptoms in a subset of people.

The key thing to understand is that your brain isn't working in a stable hormonal environment; it's constantly shifting. And those shifts can directly affect how your ADHD shows up.

Estrogen, dopamine, and why “low” feels harder

ADHD fundamentally involves differences in how dopamine works in the brain circuits that control motivation, attention, and executive functions. Estrogen affects both dopamine and serotonin systems; it generally helps make these neurotransmitters more available and effective, which tends to support better focus and emotional regulation. [2]

When estrogen drops in the week before your period and at the start of bleeding, you lose that supportive effect. This can reveal or worsen ADHD struggles like trouble focusing, difficulty starting tasks, and getting frustrated easily. For a brain that's already dealing with less efficient dopamine signaling, dropping into a low-estrogen state can feel like getting hit twice; things that were manageable before suddenly feel impossible. [4]

This pattern aligns with what a lot of people report, that their ADHD feels easier to manage when estrogen is higher (around ovulation and early in the cycle) and much harder right before their period.

Progesterone and emotional reactivity

Progesterone rises after ovulation and stays elevated for most of the second half of your cycle, then drops along with estrogen right before your period. Progesterone and its metabolites are thought to interact with GABA receptors in your brain, which affects anxiety levels, how sedated or alert you feel, and your overall emotional state. [1]

Some people find that progesterone in the second half of their cycle makes them more irritable, emotionally unstable, or anxious, especially when hormone levels shift rapidly at the end of the cycle. When you add that on top of the emotional dysregulation that already comes with ADHD, it can make premenstrual distress much worse. You might find yourself getting into more arguments, feeling extra sensitive to rejection, and experiencing intense mood swings. [6]

Common symptom patterns before a period

When people track their ADHD symptoms throughout their cycle, a few clear patterns tend to show up again and again in clinical reports and patient surveys.

Cognitive symptoms: Increased brain fog, slower processing, greater distractibility, and difficulty holding multi‑step plans in mind in the premenstrual week.

Executive function: More procrastination, disorganization, missed appointments, and difficulty prioritizing tasks as the period approaches.

Emotional symptoms: Heightened rejection sensitivity, irritability, tearfulness, and shame after mistakes, often overlapping with PMS or PMDD features.

Behavioral patterns: More impulsive spending, overeating, doom‑scrolling, or other short‑term reward‑seeking behaviors, consistent with hormone‑modulated reward circuits in ADHD.

Medication response: Some patients report that stimulants feel less effective or “flatter” in the late luteal phase, with small case series suggesting decreased premenstrual stimulant response in some individuals.

Premenstrual disorders and ADHD

PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder) is a severe cyclical mood disorder that causes significant distress and impairment in the week or two before your period. Growing evidence shows that ADHD and PMDD often occur together, and that neurodivergent people may be more sensitive to hormonal changes. [5]

If you have both ADHD and PMDD, you might face a monthly cycle where intense mood symptoms, depression, anxiety, rage, and hopelessness pile on top of an already struggling executive function, which can disrupt work and relationships. Then, when symptoms lift after your period starts, you might question whether it was really that bad, or feel gaslit, especially if your doctors haven't talked to you about cycle-related symptom patterns. [5]

Why is this pattern often missed?

Historical research gaps: Most ADHD trials historically excluded menstruating participants or did not analyze outcomes by cycle phase, leaving a limited evidence base on hormonal modulation.

Normalization of suffering: Cultural narratives that periods are “supposed” to be miserable lead many people to normalize severe premenstrual impairment instead of seeking evaluation.

Fragmented care: Gynecologists, psychiatrists, and primary care clinicians may each see part of the picture (PMS, mood swings, ADHD) without integrating them into a single understanding.

Self‑blame: Because symptoms improve after the period, people often label themselves as inconsistent or weak rather than recognizing a predictable biological trigger.

Tracking your own pattern

Just tracking your symptoms alongside your cycle can be a great way to document and validate that your ADHD gets worse premenstrually. Over two or three cycles, many clinicians recommend keeping track of:

Cycle day relative to bleeding

Ratings of focus, task initiation, organization, and forgetfulness

Mood and anxiety ratings, including rejection sensitivity and irritability

Sleep, pain, and other physical symptoms

ADHD medication dose, timing, and perceived effect

Even simple 1-10 scales jotted down in your notes app can show you that certain days, like days 24-28 in a 28-day cycle, are consistently worse. Having this data makes it easier to talk with your doctor about adjusting treatment and takes the guesswork out of remembering how you felt weeks ago.

Management strategies that might help

Planning your cycle: Try scheduling demanding tasks during the weeks when estrogen is higher, if you can. Build in extra support during the premenstrual week, more reminders, simpler to-do lists, and fewer commitments. Prioritize sleep, eating well, and moving your body in the week before your period, since being tired and blood sugar swings make ADHD symptoms worse. Basically, treat your menstrual cycle like a predictable factor you can plan around, kind of like how someone with asthma prepares for high-pollen days.

Adjusting ADHD medication: Some small clinical reports and expert opinions describe women with ADHD who do better when they temporarily increase their stimulant dose during the premenstrual week; they focus better, feel more stable emotionally, and tolerate it fine. One case series found that adjusting stimulant doses based on cycle phase reduced premenstrual symptom spikes without serious side effects. Though we still need larger, more rigorous studies to confirm this approach. [2]

Treating PMS or PMDD: Standard treatments for PMS and PMDD can really help reduce premenstrual mood issues and functional struggles when you're also managing ADHD. SSRIs are one option; you can take them every day or just during the second half of your cycle, and there's solid evidence they work for PMDD. Therapy focused on emotion regulation, handling distress, and being kinder to yourself during rough weeks can also make a difference. And lifestyle changes like regular exercise, cutting back on alcohol, and having structured ways to manage stress can modestly improve your mood and energy before your period.

Research on ADHD, sex hormones, and the menstrual cycle is still evolving, but what we know so far supports something practical: for many people with ADHD who menstruate, those premenstrual symptom spikes are real, they make sense biologically, and you can actually do something about them. [4]

Tracking your symptoms, making environmental adjustments, and—when it makes sense—adjusting medication or trying hormonal strategies can all help. Your lived experience is key here. When you track what you're going through and bring that into conversations with knowledgeable clinicians, you're much more likely to find an approach that actually works for you.

References:

[1] Eng, A. G., Nirjar, U., Elkins, A. R., Sizemore, Y. J., Monticello, K. N., Petersen, M. K., Miller, S. A., Barone, J., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., & Martel, M. M. (2024). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the menstrual cycle: Theory and evidence. Hormones and Behavior, 158, 105466.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0018506X23001642

[2] Mannion, K. (2025, June 9). ADHD and hormonal changes in women. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/adhd/adhd-and-hormonal-changes-in-women

[3] van Anders, S. (2023, July 10). ADHD symptoms can fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/adhd-symptoms-can-fluctuate-with-the-menstrual-cycle/

[4] Broadway, C. (2024, January 3). Low estrogen and ADHD: Hormones impact symptoms during menstrual cycle. ADDitude Magazine. https://www.additudemag.com/low-estrogen-adhd-hormones-theory/

[5] ADDA Editorial Team. (2025, February 27). PMDD and ADHD: Understanding the connection and managing symptoms. Attention Deficit Disorder Association. https://add.org/pmdd-and-adhd/

[6] Raczkiewicz, D., Jaskulak, M., Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U., Darmochwal-Kolarz, D., Kosinski, P., & Owczarek, A. J. (2023). Progesterone and Its Metabolites Play a Beneficial Role in Affect Regulation in the Female Brain. Pharmaceuticals, 16(4), 520. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/16/4/520